Thursday, July 17, 2008

July 25, 1968

The sexual revolution had particular hopes for July 1968. The previous forty years had seen almost every Protestant church come out with an acceptance of chemical birth control, beginning with Anglicans in 1930. The Catholic Church set up a commission in 1963 in order to explore these matters, and many hoped it would follow the way of the Anglicans and other Christian denominations. Instead, on July 25, 1968, Paul VI published Humanae Vitae, and the Church has been criticized from within and without on this subject more than almost any other. Very few of these critics even attempt an understanding of the reasons for the Church's continual rejection of artificial contraception or even question the widespread acceptance of hormonal birth control.

The family is the basis for society. If, like St. Benedict, we are going to build a new society, we must start with the family and developing a better understanding of the family.

So, here's to you, Humanae Vitae, on your 40th anniversary!

An exerpt of Benedict XVI's speech in honor of the anniversary: "In fact, conjugal love is described within a global process that does not stop at the division between soul and body and is not subjected to mere sentiment, often transient and precarious, but rather takes charge of the person's unity and the total sharing of the spouses who, in their reciprocal acceptance, offer themselves in a promise of faithful and exclusive love that flows from a genuine choice of freedom. How can such love remain closed to the gift of life? Life is always a precious gift; every time we witness its beginnings we see the power of the creative action of God who trusts man and thus calls him to build the future with the strength of hope."

Monday, June 16, 2008

We Are What We Listen To

I think as Catholics, if we want to win the culture wars we need to seize control of the media in a way that we are currently not doing. While it is good that Catholic radio has great apologetics explaining the faith, what we need is to feature music and create a music industry that reflects beauty and stirs the soul. Unfortunately, I don't think that is happening. Through music, we need to make the fullness of truth beautiful so that a secular person may stumble across it on the radio dial and feel their soul uplifted and drawn in to a deeper reality. That should be the vision for Catholic radio.

Saturday, June 14, 2008

State of Marriage

This article is a pretty good commentary on the use of language in this political battle, and the call for Christians to go to work like we did in the days of the old pagan Roman empire.

http://www.catholic.org/politics/story.php?id=28225&page=1

Monday, June 2, 2008

Faith and Art

Thursday, May 1, 2008

Heretics as Theology Professors at a Catholic Universities?

In your response please indicate what you believe the mission of a Catholic university is and how the answer to this question best addresses this mission. My response will come when I have a bit more time to write.

Oh, and Ana Maria, great post about the common denominator discussion.

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

Common Denominators

It is important to distinguish these three ways of relating to other people because it affects how we react to them. Oprah seems to be appealing to the deepest desires of our hearts and proposing that many different ways of getting to God may make one happy/fulfilled. The Christian proposal is that this isn't true, that God Incarnate is the only being or thing that can fulfill those desires. If people recognize the deepest desires of their hearts, then we are able to make this proposal to them.

Normally, however, people do not recognize their desires, or, if they do, they are not able to distinguish between their deepest desires and their instinctual desires. If we are aware of this difference, then we are able to educate ourselves and others to discover the difference between our elementary desires and our instinctual desires. Then we are able to better follow our elementary desires, which, if the Christian proposal is correct, will lead us to Christ.

When we talk with people about common experience, even if that experience is of pop culture, we are able to help educate them (and ourselves) to our desires. If someone likes fashion, we penetrate and ask why. What is it about fashion that's appealing? Well, it is beauty. Overtime, our elementary desires come out.

Educating ourselves and others to the desires of our hearts is the method proposed by Luigi Giussani, the founder of Communion and Liberation. It is, in the (post?)modern world that prizes the individual and the individual's desires, a very accessible method because the starting point is the individual and the individual's desires. This method begins with Giussani's books The Religious Sense and continues with At the Origin of the Christian Claim and Why the Church?

Monday, April 28, 2008

LCD, Pluralism, and the Media

Alberto makes a great point in saying that the enjoyment of superficial things is not necessarily a bad thing. If anything, it can bring us together. I agree with this on many fronts. For myself, because I enjoy all the major sports, I find it much easier to talk to guys. If I meet a completely random guy, I can strike up a conversation about a game or a team and we can get along. Similarly, someone told me about the philosophy about talking about the weather. No matter how different you are from someone, no matter how little it appears you have in common, you are both share the weather outside and that's not a bad starting point for conversation.

In that sense, I don't know if lowest common denominator is the right term for what I'm trying to describe, so maybe you all can help me find another term. What I'm referring to is the "it's not polite to talk about politics or religion at the dinner table" kindof attitude. It's a not talking about the things that matter most because it raises tension, people don't budge in their beliefs, and we don't move forward as a society. It's not bad to talk about the weather or superficial things like sports, TomKat, or Shakira. But if that is all you are talking about, if as a society we can't or won't talk about the things that matter most in a meaningful way, what does that mean for our intellectual and political life?

I do think the superficialness has something to do with the sloth of materialism, but I also think it's related to a relativism that's manifested in a politically correct pluralism. If I have a friend who is an atheist, our religious conversations would focus on whether or not there is a God. We couldn't reach the truth about the Eucharist without the foundational piece of agreeing there is a God. Apply that to multiple perspectives on the meaning of life, and given that our media likes to challenge and question the very foundational things that we consider a basic part of our humanity and the natural law, and it's easy to see why it's so hard for popular culture to dive with any depth into truth.

As a result of not diving into truth, the media tries to be "neutral." However, I don't think there is such a thing as an unbiased, neutral media. In merely picking what they choose to be news and what they choose not to report, what they choose to make the headline and what they don't, they are making decisions on what's important by a set of values. I think our contemporary media uses Enlightenment values, underlying in relativism. But that's not being neutral.

Media should report things with an understanding of the good, the true, and the beautiful. Can such a media be a successful mainstream outlet in modern America? What would it like? Is this part of the key to saving Western Civilization?

Saturday, April 26, 2008

Percy's Response to the Lowest Common Denominator

Friday, April 25, 2008

Lowest Common Denominator of What?

The problem with Oprah's cult, sexy commercials, and nutrigrain is that each takes that desire and directs it towards an incomplete and unfulfilling end. The desire itself that each taps into, the desire for the infinite (manifest in spirituality, in sex, and feeling great) is fundamentally good. The reason each appeals to any kind of common denominator at all is because each appeals to our fundamental desire for the good. But they redirect us to an unfulfilling end, an end that won't fulfill those desires. Those things gives us a incomplete solution to the fundamental problem of our humanity, which is why each of them leaves us, in the end, feeling isolated and incomplete. But the problem is not that they appeal to the lowest common denominator, but its that they appeal to it without giving any real solution or fulfillment.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Lowest Common Denominator and Oprah

I bring this all up because I think this is what Oprah is trying to do in promoting and offering web seminars on Ethan Tolle's book A New Earth. Through the promotion of this book, Oprah is promoting a religion based on New Age philosophy that teaches there are multiple, equally valid ways to get to God, (and Jesus is only one of these ways as Oprah explains here to this Catholic woman) and God is "a feeling experience and not a believing experience." This is a brilliant use of the lowest common denominator strategy. If you're going to sell something like religion in pluralistic, pop culture America, it doesn't get much lower than "there is no one way". Nevermind that Jesus himself said, "I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me" (John 14:6) and nevermind that the claim that "there's no one way" is itself a one way narrow minded view of religion. Somewhat related to this topic is this clip of Oprah getting called out on this point by an audience member in the middle of Oprah's show.

Now, this all relates to our conversation on the best way to influence/change Western civilization. Just as St. Benedict had a method, so does Oprah. Use mass media to have a show that focuses on feel good lowest common denominator subjects. As people can relate their own experience and humanity to the topics of the show (since it is lowest common denominator stuff, it's easy to relate to the subject matter), you earn the people's trust. Then you slowly lead them to a new philosophy and a new religion. As a billionaire, and one of the most powerful and successful people in the very influential mass media, who would dare speak out against Oprah's version of the meaning of life?

Ironically, it's the democratization of the Internet that is leading the charge in calling out Oprah. I first read about this issue a little over a month ago from this article posted by LifeSiteNews.com. Apparently, this wasn't the only site as blogs and YouTube have generated a buzz about this and put it on the radar of the mass media. At the center of it, apparently is this YouTube video that makes the claim that Oprah is starting a cult, which has over 5 million hits. Then Fox News ran this story, asking the question "Is Oprah starting her own cult?" CNN put their finest intellectual and theological experts on this question in this completely unbiased reporting clip. I wonder if CNN's coverage of this topic has anything to do with the fact that Oprah.com is linked to CNN's frontpage.

I view this as a modern day David vs. Goliath. Here you have a billionaire that is the queen of mass media trying to start a religion based on the media values of the lowest common denominator against a handful of unfiltered bloggers and amateur YouTube video producers, who wouldn't have even had a voice but a few years ago. I am real curious how this will all shake out.

Monday, April 21, 2008

More about "The Meeting"

Pope Benedict XVI, in his pre-papal days as Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, was the curial official who read every case file that Boston, or any other diocese, had to hang their heads over. He has read every person's account. Felt, in a way, the pain and hurt that each of these youngest members of Christ's faithful suffered at the hands of who were supposed to be Christ. While the gears of the Church move quite slowly, I think this Pope had to visit with these people, not because he is the leader of the Church whose ministers harmed them, but as a priest himself, as a bishop himself, he had to apologize directly and in-person to at least a few of those harmed by his brother priests and bishops.

As for why this was on the public schedule, this was not a public, or semi-public event. This meeting was almost confessional in nature; this was not to publicly acknowledge past faults of the Church (or members of it) but for a pastor to talk to individual members of his flock. If it was a public event, pre-scripted as many of these Vatican events are, it would be exactly not what the Pope wanted to do. This was a time for him to listen, for those hurt to tell him whatever they wanted. As one of the gentlemen said to CNN later that night, they were never told that they could not say anything. Of the three interviewed, two seemed at some level of peace, but the third still seemed quite angry. That is what Pope Benedict wanted; he wanted to hear the actual voices, as they are, of these faceless, haunting case files he read for years before rising to the Chair of Peter.

What will change in the American Church out of this? I don't know. This crisis is something that virtually no one saw coming or had any idea to expect it. There's no frame of reference to compare this situation. Time will tell.

Back to Beauty

Sunday, April 20, 2008

BXVI in NYC: Fake Birds

BXVI in NYC: Harry Connick, Jr

BXVI in NYC: Jose Feliciano?

BXVI in NYC: I stand corrected.

BXVI in NYC: Empty Seats?

BXVI in NYC: I can see the back...

Friday, April 18, 2008

The Meeting

Some have asked how the six victims who met the pope were chosen? Were they handpicked because officials knew they would not cause controversy or challenge the pope to act? And why was the meeting private, when a public forum could have brought together many more victims?

I think these are very reasonable questions for people to ask, especially for those who have been terribly injured by the Church. But I think the venue Benedict chose was very fitting for his mission. Unlike at John Paul's meeting with Agca, here there was no press, no photo-ops. Rather, there was an intimate and free encounter in which Benedict first and foremost exercised his role as spiritual father. Those victims who were present and whom I saw interviewed were most impressed by his fatherly presence, calling him a grandfather who, as he listened, they knew understood and cared.

Those who met the pope had met before with other bishops, and they have learned to judge whether someone with authority cares about them and takes them seriously. I'm sure some bishops they have met have not been convinced of their stories, or have taken a coldly doctrinal or legalistic perspective. Benedict's second purpose, I believe, was to set an example to American bishops, who deal with this crisis on a daily basis. A leader is meant to listen and to be a father more than an administrator.

Benedict also set an example for all of us. Imagining the pope hearing such horrible stories that must shake even his faith reminds me of times I have spoken with people, whether young or old, who have been scarred. I think especially of my time as a volunteer hospice chaplain. These encounters often produce anger and frustration in the one who listens, which facilitates solidarity with one who suffers. The pope came to America not only to speak with us, but to learn from us and experience the pain our nation's Church has been through. The encounter the pope had with abuse victims is transformative not only for victims, but also for the pope. How he will be impacted and impelled to new action remains to be seen, but his visit was an important beginning and established, in imitation of Christ, a strong solidarity with and presence to victims. Action and reform ("doing") is always second to presence ("being").

I take the pope's initiative as a call for each of us to openness and dialogue, even the most difficult conversations. We must be ready to experience someone else's perspective, to listen attentively, and to be changed by what we hear. Thus this private moment of his visit is an embodiment of his commitment to dialogue, peace, and pluralism, which he has touched on throughout his talks and which resonate so well with our American heritage.

BXVI in NYC: Helicopters Overhead

While on the approach ramp, I saw a low-flying NYPD helicopter. This IS New York, so I thought nothing about it.

Moments later, I saw three very official-looking helicopters heading from the Queens/JFK-area that reminded me of what Marine One looked like from The West Wing and all were heading toward where the UN is located.

NYPD helicopters were circling the site where I lost sight of the desending helicopters.

Thinking this all was a bit odd, even for New York, I checked my watch-10:00ish-and called my Pope-obsessed friend Hung. Sure enough, the Pope's schedule had him in route from JFK to the UN via helicopter about that time.

If I'm lucky, he looked down upon the Brooklyn Bridge at that moment and blessed the people on it.

This isn't an academic post, but it is about me literally Waiting for Benedict.

(Note: I'm writing this from my BlackBerry while on a train so I'll add links and the category tonight when I settle in.)

Thursday, April 17, 2008

BXVI in NYC: Pope of the Internet

Last night, I was interviewed by KEYE CBS 42 for a set of pieces they're putting together about the Papal visit; the first one with me was aired last night at 10 pm. I've seen myself in HD—somewhat scary, but I digress. In that interview, I mentioned that one of the aspects of Pope Benedict that makes him unique is his status as Pope of the Internet.

Pope John Paul II, of happy memory, was considered the Pope of TV. Anyone who saw any images—stills or video—were inspired by him. Whether it was the picture of him standing in front of a teepee in Native American-styled vestments or with sunglasses on or holding his cane upside down acting like it was a hockey stick, you felt a connection to him. He wrote many profound things, and by all means, they should be read and examined. His Theology of the Body and texts examining the role of Mary were groundbreaking in many ways, but he is remembered by the way he captured people.

Pope Benedict XVI is different. He's cute and hearing him with his German accent is great, but he is much more reserved than John Paul II. I can't imagine Pope Benedict ever using his cane as a hockey stick, for example. His gifts, however, lie with the written word. You may hear, or not, the Pope speak, but you want to go online and download the text. His gift isn't in the presentation of Truth, but in his explanation of the Truth. By training, he is a teacher, serving as a professor in Germany before being called up to the Major Leagues (in reverent terms, the fullness of priesthood as a bishop and then to Rome to serve in the Curia) and his natural gift for teaching is obvious.

He teaches when he speaks—from his weekly General Audiences to his Apostolic Exhortation on the Eucharist to the Moto Proprio allowing for the more widespread use of the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite to, of course, his encyclicals, God is Love and Saved by Hope. Now three years after he was called to the Chair of Peter, Pope Benedict still has more people attend his General Audiences than our rock star John Paul II did. Why? Because they learn from this teacher. This is not to say anything negative about John Paul II, not at all, but only that the timid, quiet German who many consider quite dry has a mystical attraction that people are drawn toward through his catechesis.

The Internet is Pope Benedict XVI's biggest aid in his efforts. In the days after any text of his is released, people from around the world are reading it, discussing it, sharing it, wrestling with it and ultimately, finding a greater understanding of the Catholic faith.

I haven't had the chance to read the full-text yet, but apparently, what he had to say to the United States' bishops last night is worth the read.

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

Simply Put: A Man of Peace

Before today, as a Catholic, I thought the answer was more-or-else straight-forward: the head of the Church and Christ's victor on earth. Today I learned the answer was far, far more simple.

It was about 5:20 when I had the opportunity to see the Pope pass by in his custom-built Popemobile. He came by slowly. Inside the car's glass bubble, this humble priest smiled and waved to the crowd, and since he drove slowly, he took the time to look at us each individually. His glance was full of life and his spirit radiated a glowing and unmistakable message: peace.

Today the Holy Father became for me a messenger of peace. So often political leaders and others talk of peace, but this man lives it. And it shines forth in his life. His predecessor John Paul II was a rock-star, and his example of faith drew an enthusiasm for Christ, especially for we the young. Benedict's personal presence makes a invitation quiet invitation: to think, to reflect, and to attempt to live peace. His message has been so simple since the beginning of his Papacy, and his them for this trip, Christ is Our Hope. Nothing could possibly be more attractive

Given this man's wisdom, even more exciting than seeing him is listening to his words. And his message to the Bishops inside the Basilica was quite simple: pray, pray, and pray. And he preached by example tonight, leading the Bishops in the traditional prayer of psalms and hymns that all priests and many lay Catholics say daily. That Christ's messenger of peace would lead through the example of his life of prayer with all of us speaks volumes to me. It is a silent invitation that I know he invites each of us to share in our lives and with each other.

That's who is the Holy Father: A man of prayer. A Man of Peace.

President and Pope, Together

A brief excerpt about freedom from the Pope's speech:

In a word, freedom is ever new. It is a challenge held out to each generation, and it must constantly be won over for the cause of good. Few have understood this as clearly as the late Pope John Paul II. In reflecting on the spiritual victory of freedom over totalitarianism in his native Poland and in Eastern Europe, he reminded us that history shows time and again that “in a world without truth, freedom loses its foundation,” and a democracy without values can lose its very soul. Those prophetic words in some sense echo the conviction of President Washington, expressed in his Farewell Address, that religion and morality represent “indispensable supports” of political prosperity.He mentions Washington's farewell address, which is worth a read for anyone interested in understanding Washington's fears and hopes for the new nation. Perhaps best known for Washington's clear repudiation of all wars over the interests of foreign nations, he also has some choice words about morality and religion:The Church, for her part, wishes to contribute to building a world ever more worthy of the human person, created in the image and likeness of God. She is convinced that faith sheds new light on all things, and that the Gospel reveals the noble vocation and sublime destiny of every man and woman. Faith also gives us the strength to respond to our high calling and to hope that inspires us to work for an ever more just and fraternal society. Democracy can only flourish, as your founding fathers realized, when political leaders and those whom they represent are guided by truth and bring the wisdom born of firm moral principle to decisions affecting the life and future of the nation.

Let it simply be asked, Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in courts of justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

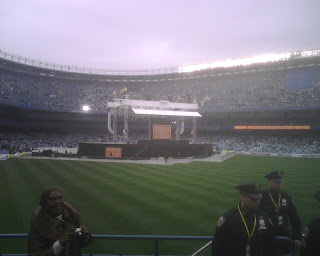

BXVI in NYC: The Ticket

For everyone that didn't know, I was able to land a ticket to the Papal Mass at Yankee Stadium this Sunday. I'll be flying up to NYC on Thursday and with my trusty cell phone camera, will be "reporting" on aspects of the trip--visits to any particularly interesting sites and the Papal Mass itself.

My apologies for the poor image quality-my cell camera isn't great-but below is a picture of my ticket.

Monday, April 14, 2008

Only Something Infinite Will Suffice

An excerpt:

Benedict has appealed often in his pontificate to natural law, but it is a natural law that has recuperated its finality and center in God. He affirms and develops Aquinas‘s understanding of the natural moral precept to seek to know the truth about God and to live in community with others. Note that Benedict emphasizes the nature of law as a matter of desire and thus love, in contrast to the modern tendency, following Kant, to conceive law more basically as duty. As emphasized in his first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est, what the human being desires (eros) is most basically to love God above all things and others for their own sake (agape). The point is thus that this desire to love God and others generously arises naturally. It is not merely a function of grace, although the desire is fully realized only in grace.Seriously, check out the whole thing. Its very well done, and gives a great degree of insight into what to expect from Benedict this visit.

The task of Christians, then, is to awaken this desire and give witness to it: to show that the restlessness driving every act of human consciousness in its depths is–even in America–a restlessness for God and for love. This is what is meant by the pursuit of happiness, rightly conceived.

Saturday, April 12, 2008

Pope Benedict on St. Benedict

1) The context of the times of St. Benedict:

Between the fifth and sixth centuries the world suffered a terrible crisis in

values and institutions, caused by the collapse of the Roman Empire, the

invasion of new people and the decline of customs. By presenting St. Benedict as

a "shining light," Gregory wanted to show the way out of “this dark night of

history” (cfr. John Paul II, Teachings, II/1, 1979, p. 1158), the terrible

situation here in the city of Rome.

Compare to the Pope's description of the context of contemporary Europe:

Today, Europe -- deeply wounded during the last century by two world wars and

the collapse of great ideologies now revealed as tragic utopias -- is searching

for it's own identity. A strong political, economic and legal framework is

undoubtedly important in creating a new, unified and lasting state, but we also

need to renew ethical and spiritual values that draw on the Christian roots of

the Continent, otherwise we cannot construct a new Europe.Without this vital

lifeblood, man remains exposed to the ancient temptation of self-redemption -- a

utopia, which caused in various ways in 20th-century Europe, as pointed out by

Pope John Paul II, “an unprecedented regression in the tormented history of

humanity” (Teachings, XIII/1, 1990, p. 58).

One thing that is awesome about the Catholic Church is that it sees history through a much longer perspective than other institutions. This is especially true compared to political institutions in which politicians have such a narrow time frame to "demonstrate results" to the electorate in order to ensure their survival. While the Holy Father has great concern for a Europe that has lost its identity, he is not afraid. Rather, his attitude demonstrates a confidence in how God works in history and a confidence in Jesus promise that the gates of hell would not prevail against the Church. Instead of being frantic, the attitude of the Pope is more like, yes the times are troubling, but we've seen this before and we know how we came out of it before, and with God's grace and the model of St. Benedict, we can come out of this again.

2) Benedict starts with the renewal of himself first:

Benedict firmly believed that only after conquering these temptations would heThis reminds me of my favorite quote from the Tao Te Ching, which goes something like this: "A man who attempts to change the world without first changing himself, is like a man who tries to cover the whole world with leather in order to avoid stepping on sticks and stones. It's much easier to wear shoes." Authentic comes best when we become, we personify, the change we want to see in the world.

be able to say anything useful to others in need. And so, having pacified his

soul, he was fully able to control the drive to put oneself first, and so became

a creator of peace. Only then did he decide to found his first monasteries in

the valley of Anio, near Subiaco.

3) The monastery and the relationship between isolation and public life:

According to Gregory the Great his exodus from the remote valley of Anio to

Mount Cassio -- which dominates the vast planes around it -- is symbolic of his

character. A monastic life of isolation has it's place, but a monastery also has

a public aim in the life of the Church and society as a whole. It must serve to

make faith visible as a force of life. In fact, when Benedict died on March 21,

547, through his Rule and the Benedictine order that he founded, he left us a

legacy that bore fruit all over the world in the subsequent centuries, and

continues to do so today.

So this shows that to be set apart is not mutually exclusive from playing a part in public life. We can both be isolated in a privacy to cultivate our values, and at the same time be a visible shining light for those that might be in the fog of confusion of public life and values. I think Anamaria brings up a very good point in asking how to do this concretely. While I have yet to formulate a response to this, I think it is an important discussion for those on this blog to take up.

Friday, April 11, 2008

Eye of the Beholder?

As to the first, the author of the article makes the point that beauty is the catalyst for our pursuit of goodness and truth. That is, "Without beauty, truth becomes legalism and goodness becomes moralism." Beauty is the thing that makes us, as humans, attracted to the true and the good. It awakens us to the desire. It is the thing that moves. A person can tell me something true, but without it being beautiful, I won't care. I can realize something is good, but without beauty, I won't do it. As a result, the Catholic Church's mission of teaching the true and the good can only occur in the context of the beautiful. It is what gives us ears to hear the truth. It is what gives us the will to do what is good.

And for the second, to say that beauty is pluralistic is not to say that it is relativistic. That is, the fact that some things move me more than Francisco, and vice-versa, does not imply that nothing is objectively beautiful. Honestly, I think it is kind of like Kraft's point about lay movements: there are several good lay movements, some which move me more than others. But there are also some movements that teach heresy. A great many might be objectively good, but there are still some that are objectively bad. And a great many things are beautiful, but there are also some things that are just plain ugly.

Perhaps more importantly to me personally is what this kind of a view of beauty does to art education. The entire idea behind art education is that something is objectively beautiful and that we can be taught to better appreciate it. But if there is nothing that is objectively beautiful at all, there is no point in being taught to appreciate one thing more than another. Preference reigns supreme. I think this strikes me so strongly because art, particularly music, is something I'm only now, as an adult, learning to appreciate.

Even after gaining an appreciation, the best art takes patience and attentiveness to get its beauty, while pop stuff is immediately catchy (though often superficial). For instance, when I was first given a copy of Sufjan Stevens' Illinois, I couldn't stand it. His eight minute "orchestral folk" songs seemed strange and noisy, and I longed to be back among my three minute, always catchy pop songs. Now, though, after roughly a thousand listens, the album stands among my favorites. And it is without question a beautiful work of art. I stuck with it because I had people who I trusted to have an eye/ear for beauty telling me it was beautiful, even when I didn't get why. But if I had accepted that beauty was in the eye of the beholder, I would have had no reason to wait, to educate my sense of beauty. And I do believe that I know God better as a result.

The Nation State and the Common Good

We do not ask for salvation from politics. We cannot expect politics to do this either for us or for others.

The tradition of the Church has always indicated two ideal criteria for judging every civil authority and every political platform:a) libertas Ecclesiae. A power that respects the freedom of a phenomenon so sui generis as the Church is for that very reason tolerant towards every other form of authentic human aggregation. The recognition of the role of faith, including its public role, and the contribution it can make to man’s journey is, therefore, a guarantee of freedom for all, not only for Christians.

b) the “common good.” A power that it is conceived as a service to the people has at heart the defense of those experiences in which the desire of man and his responsibility can grow as a function of the common good, through the construction of social and economic works, in keeping with the principle of subsidiarity, well knowing that no program will enable it to be fully realized because of the intrinsic limitations of all human effort.

For a bit more commentary on them, check out Rick Garnett's post over at Mirror of Justice.

Lay Ecclesial Movements in Parish Life

While the most primal unit of the Church is the domestic church, that is, the family, our faith finds its fruitfulness when we interact with other domestic churches in the parish. The parish is intended to be the center of the local Catholic community; much like a town or city, every member of the parish is not identical, nor even close. On every issue, people of different minds come together in local community to celebrate the Living and True God, and we are enhanced by seeing these differences. There is a great difficulty in cursing the local city council member's decision on a vote to rezone land near you when you see him every Sunday singing in the choir, when you know him and you know he is doing the best he can to be a faithful person, true to himself. Beyond that Jesus Christ lived, suffered, died and rose again for us, there may be nothing else you hold in common with some fellow parishioners.

Without ecclesial communities, we may feel, at times, alone within the parish. While you may share a great devotion to Mary by way of a certain revelation or to a certain aspect of the Catholic theology of work, it can be quite difficult to find someone like-minded who can help you grow within philosophy. Ecclesial movements enable the faithful to find people who they may align with the greatest in terms of spirituality and philosophy and that is truly great.

However, the parish needs you too! The parish is not, and should not be, a home to those who have not found an ecclesial movement, or have no idea what one is, or who feel no need to seek out such a community. The parish is home to all of us.

Ecclesical movements bring new spiritual fruits to members, and members in turn have an obligation to share what is given to them. For me, I may feel called to one group, really dig into the spirituality of that group and come from that with a new understanding about an aspect of being Catholic. For you, you may not feel called to that group, the spirituality may not enrich you personally, but by my sharing of my new understanding, you were able to see something in a new or different way that enhanced your walk along the pilgrim pathway toward salvation. Likewise, the reverse is true, whatever you gained in your spiritual journey, with a movement or not, is a gift that can help me along my journey.

These new movements are inspiring a New Springtime within the Church, but all should see the fruits.

Thursday, April 10, 2008

American Pop Culture and the Catholic Church's Role in Saving Beauty

Beauty as a mysterious, transcendent force is conspicuous by its absence in

American culture. If we divide culture into high and low, or intellectual and

popular, then we are forced to admit that pop culture has no authentic beauty

and high culture has divorced whatever beauty remains from truth and goodness.

Pop culture’s assault on beauty is too wide-ranging to elucidate here.

“Pop” may be “popular” abbreviated, but it also calls to mind brands like Coke

and Pepsi—producers of something fizzy, sweet, briefly stimulating, and rotten

in the long-term. Pop culture is junk culture. Its invitation is not to “savor

life” but rather to exploit it for the sake of instant gratification. It is

designed, manufactured and marketed to be consumed and thrown away.

When it comes to American pop culture, Beauty faces an uphill battle. If

you’re addicted to crack it’s difficult to appreciate a bottle of vintage

Bordeaux. Moral ugliness is given a surface-level spit-and-polish and the

results include: The Da Vinci Code, soap operas, E! television, daytime

television, crass commercials, American Idol, infomercials, Sex and the City

(okay, with a few exceptions let’s say “TV” in general and have done),

mass-market paperbacks, shallow self-help books, glossy magazines lining

checkout counters with covers featuring either airbrushed supermodels or

Photoshopped aliens (who can tell the difference?), summer movies with big

explosions, Paris Hilton and Britney Spears and their paparazzi photo-ops,

cookie-cutter sequels, lowest-common-denominator plot formulas, on and on ad

infinitum. In the superficial realm of popular culture, “beauty” is a concept

co-opted by Cosmopolitan to sell more magazines. In the prophetic words of Hans

Urs von Balthasar, pop culture makes of beauty “a mere appearance in order the

more easily to dispose of it.”

And then he follows that up with the Catholic Church's role in saving beauty:

The Catholic Church, perceived by many as the bulwark of conservative, outmoded,

antiquated values, will only survive by being counter-cultural. We are no longer

part of an epoch that produced Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael as a matter

of state and Church policy. As soon as the Church kowtows to pop culture in the

guise of groovy services or to high culture in the guise of ghastly-looking

modern churches then there is trouble in paradise.

I've always thought of the Church's role in the world as preserving the good and the true, I've never considered its role in preserving beauty from a pop culture that has a limited view of our humanity. This thought is intriguing , until the author makes fun of the song "Eagle's Wings" and the folk mass. I, for one, really like that song and I enjoy folk masses. I don't think my enjoyment of that form of music makes me barbarically uncultured.

This illustrates that the difficulty of tasking the Catholic Church with the role of preserving artistic beauty from pop culture is that the Church does not have a clear standard to distinguish between what is beautiful and what is not. With faith and morals, the Church can point to the reality that God became flesh and taught us truth and objective morality, and that the Church has been tasked with safeguarding these truths throughout time. I don't think the Church has that same claim on its ability to judge beauty. I think the best the Church can do is teach truth and morality so man can flourish in his humanity and use his free will to create beauty.

Thoughts?

Recognition of Beauty and Living in the Present

Benedict on Benedict - uncut director's edition

Getting Past the "Nation State" Mantra

In addition, though, I'd like to ask this, of her and of anyone else who cares to answer. If we are to think in terms of what we, our small communities, can do about local and global problems, can we also think in terms of the nation state? Or does the one preclude the other?

This issue, or something like it, is one I've long struggled with no little or no avail. On the one hand, I buy Aquinas's argument that the law has an important teaching function, and that this teaching function is an important part of achieving the common good in a given society. At the same time, Cavanuagh's point that the nation state's purpose was never the common good and was always consolidation of power strikes me as fundamentally convincing. But if the nation state is not charged with the common good, if it structurally and conceptually should not be, then it seems that the laws it creates should focus less on instantiating any positive notion of the good than on simply giving people the space to create communities that can focus on such a good.

The obvious response, I think, is that, like it or not, the nation state is precisely what we have. And that despite the nation state's structural and conceptual problems, we as a citizenry have a duty to try to pass laws that serve the common good. This argument accepts the problems inherent in giving one central authority a monopoly on coercive force within a given geographic boundary as a given, but then argues that it is what we've been given so we might as well do what we can to use it as a tool for the common good.

In response to this argument, I turn to the economic theory of the second best. Second best theory relies on the assumption that if every one of a number of conditions are met, the economy will function perfectly. Its adherents argue, though, that if one of the conditions cannot be met, there is no reason to assume that fulfilling each of the other conditions will produce the best possible outcome. That is, an additional imperfection is as likely to offset the damage caused by the first as it is to compound it. As a practical example, assume that the perfect way to make a turn in my car is to slow to 20 mph and turn the wheel 20 degrees. If my brakes are out, and I can't slow to less than 45 mph, it would be ridiculous if I tried to turn the wheel 20 degrees to achieve the next best possible turn. I probably need to turn the wheel much more drastically in order to make the turn as well as possible given the condition of not being able to slow down.

I wonder if we can't apply this same reasoning to the nation state. If the nation state is a less than optimal tool for instantiating the common good, it might be that the best outcome for achieving the common good is to strip the nation state of all responsibility for it. We can accept that in the best possible society law would have a teaching function, and still we might be better off without it given the nation state's limitations.

Anybody have any thoughts? Can we give the nation state some responsibility for the common good? Or, given the obvious limitations of the nation state, must we seek the common good through local communities only?

Beauty, Conversion, and just plain Waking Up

Two immediate thoughts strike me as particularly relevant to the discussion we're having here. The first is simply that without beauty, none of us could find the infinite, the mystery, attractive at all. It is all well and good to call the truth good, but there has to be something beautiful in it for me to find it attractive. The article quote John Paul II:

Beauty is a key to the mystery and a call to transcendence. It is an invitation to savor life and to dream of the future…It stirs that hidden nostalgia for God which a lover of beauty like St Augustine could express in incomparable terms: ‘Late have I loved you, O beauty ever ancient, ever new: late have I loved you!’As such, it seems that any kind of cultural transformation has to have its roots in the beautiful. I need it to, because I'm too easily distracted by the frustrations of daily life. I need the beauty of it, the consistent and eternal newness, calling me back constantly to the true and the good.

My second thought is actually more of a question: what to do in a culture that teaches people to ignore the beauty around them and to stay focused on efficiency and production? Murphy cites a Washington Post experiment, where the Post convinced Joshua Bell, a world famous violinist, to play for an hour in the L'Enfant Plaza Metro stop during rush hour. Bell collected 30 bucks - far less than his typical $1000 hourly rate - and never had more than a couple of passersby watching at any point. However, every child who walked by tried to stop and watch. Something drew the kids to it, and something else convinced the adults to keep going.

Its seems that the starting point, then, in any sort of cultural or personal transformation has to be an awakening to the existence of the ever-present need for beauty. I have to understand that I need something else in order to seek it, and I have to understand that I need to be something else in order to become it. How do we do this, in ourselves and in the wider culture? How do I make sure that I (and those around me) are not so caught up in distractions that we miss the obviously beautiful around us?

At the end of John's Gospel, Peter and the others are out fishing when Jesus calls to them from the shore. Peter doesn't recognize Him, and keeps on fishing. But John sees who it is, telling his companions, "It is the Lord." Immediately upon hearing this, Peter dives in and swims to shore. He can't wait to be close to this source of truth, beauty, and goodness. But it takes someone else pointing out its presence to him for him to notice it at all. Is this part of the starting point? And how do we do this for each other?

Dostoevsky said, "Beauty will save the world." I believe that this is true. But in order for this to occur, we need to wake up and see it, and we need to help each other do so as well.

Wednesday, April 9, 2008

re-thinking the primacy of the nation-state

When we start to think about it, our concept of the nation-state has been imposed on us our entire educational careers. We learn about Italy in a way that makes it seem like it has always been, even though it has existed for about a hundred years. Later, we learn that nation-states have not always existed, but even as we are learning of the existence of tribes and Empires, the idea that the nation-state was always meant to be is imposed on us; we learn of tribes and Empires as silly things people did in the past, in a less enlightened time, and all of political history is culminated in the nation-state.

Honestly, I am not sure we can fully recover from this education. It takes an entire re-structuring of the way that we look at the world. To work towards this re-structuring for ourselves, I think the first step is to live in a community in a substantial way, and this community must be one that is connected to something greater other than the nation state (the Church). Then, when we discuss what "we" are going to do about the Sudan or Iraq, we think of "we" as the Church and as our small community, not as the nation-state of the United States. Our primary identity becomes our identity as Catholic, as it should be, and the Church becomes concrete in the flesh and blood people we share our lives with.

In addition, the education our children receive must be substantially different from our own. First, they must actually learn history. They must actually learn the way the tribes emerged out of the family unit, and then conquesting tribes became empires and what empires were, etc. Second, political science should be taught at a younger age, introducing competing notions of how the world should be, without introducing the nation-state as something primary.

Agreements? Disagreements?

Pope Benedict on Benedict

One of the money quotes from the article:

The "true humanism" of Saint Benedict, which means a journey toward God, remains today an antidote against the culture of the "easy and egocentric" self-realisation of man, a temptation "that is often exalted today", in a Europe that "just having left behind a century profoundly wounded by two world wars, and after the collapse of the grand ideologies, revealed as tragic utopias, is searching for its identity"....

St. Benedict in a Global Age

I would like to further explore what this looks like. In my mind, it involves living in the same neighborhood as 20-100 of my closest friends, and concretely and substantially being involved in each other's lives. I am not sure exactly how this would play out: morning prayer, daily mass, daily meals, weekly meals, a school. These questions might be best left to an individual community. In any scenario, however, we must live near one another in order to live with one another in a concrete and life-changing way. How can this happen when we all have ties to other places and other people? Do we give primacy to the community over family in terms of choosing where we live?

Tuesday, April 8, 2008

Christ fulfills culture

The paradox of the Church's history is that when she is at her weakest, when she stands no chance of overcoming the impending downfall of man, that is when the Spirit "comes to the aid of our weakness" (Rom. 8:26). Salvation history is full of almost redundant stories of Israel growing rich and lazy, and then God taking away Israel's riches and forcing her to become strong. That, I think, may be what is happening today as society and the state grow less tolerant of the moral and personalistic foundations that constitute "Life in Christ."

In terms of which model of Christ in Culture is the correct one, what makes the first two models erroneous is that operative term "total," which Christopher used to describe Christ against culture. No, Christ will never be totally against culture. But he will always challenge some aspects of every culture. Is he, then, against some things? Sure he is, and we should not be afraid to say it. Exclusively positivist vocabulary to describe the work of Christ in the world can be a turnoff for some people. God hates sin. He is against it. All cultures are infected with its cancer in some way, and that's why it is erroneous to say that Christ is totally for every culture. But human culture is not just a hive of wrongdoing, and that's why it's erroneous to say Christ is totally against culture.

If it were up to me to employ my own phraseology, I'd say Christ fulfills culture. "Culture," after all, comes from the Latin term meaning "worship." (Josef Pieper writes beautifully about this in his book Leisure: The Basis of Culture.) Culture in its purest sense is precisely the ways that persons come together to reflect the beauty and truth and goodness whose source is the divine. Culture losing its very meaning when it is not seen in relation to this original source. Christ is the one who makes man the entirety of what he was meant to be at the dawn of his creation. He "breaks down the walls of sin and division" and unites people in his Mystical Body, the Church. Culture par excellence is the Church.

In Christ "culture" fully achieves the true, the good, and the beautiful in its various arts and literature and politics etc., because Christ is himself the singular expression of all the Truths and Goods and Beauties at which those fields aim. Without him, the culture dissolves into something less than "culture" in the classic sense. It becomes a valueless state, and history tells us that those don't last very long. And when they finally collapse, what is left, through the natural course of things, is that smaller core community of persons who never took their eyes off of the true, the good, and the beautiful, i.e., Jesus.

Cultural Transformation: Time and Place for Each Model

I'm willing to concede to Christopher that for the average Catholic layman in contemporary America, to adopt the "Christ transforming culture" model makes the most sense. Our society and culture is based largely on Christian values, and for the most part, things shown in movies and in the media are a mixed bag of virtue and vice in which a properly trained Christian can distinguish between the two and choose to take what is good.

Yet, the very phrase "Christ transforming culture" is a transitional one. Christ has to be transforming culture from something (what it is) to something else (what it is meant to be). So in this model, what is Christ transforming culture to? Probably a culture more Christ-like, a culture that embraces and fosters the good, the true, and the beautiful. The French peasant philosopher Peter Maurin, who inspired Dorothy Day's Catholic Worker Movement, said that the definition of a good a society is one that makes it easy to be good. Think about that for a moment. A good society is one that if one were to get caught up and swept up in the culture, one would become a better, more virtuous person. That's awesome.

So if those adopting the "Christ transforming culture" model were really successful in creating a Christ-like culture that reflects the good, the true, and the beautiful, then the next generation would be fortunate enough to grow up in this society. In their case, adopting the "Christ of culture" model would make a lot more sense than it does now, for that culture would be a reflection of Christ. Places like the University of Notre Dame and Franciscan University of Steubenville, to a certain extent have this "Christ of culture" model of society. In those places, to get swept up in the culture is to become a more virtuous human being. That's what makes those places distinct and special.

On the opposite extreme, there's a proper time and place to withdraw from the world as St. Benedict did, though for the average Catholic layman, that time and place is probably not contemporary America. Yet, if things got much worse, if Catholic schools were outlawed and the only choices were public schools that taught all sorts of lies to our children about our humanity and our history, if Catholic professionals were being forced to violate their conscience as a litmus test for professional certification or speaking in the public square, if people were thrown in jail and sentenced to death for being and living out the Catholic lifestyle, then yes, it's very important, in that society for faithful Catholics to go underground. In fact, in the darkest periods of human history, that's what the martyrs of the early Church did, that's what the Desert Fathers and that's what St. Benedict did. The ironic thing is that from those persecutions, which led to the passionately intense small Christian communities, time and time again, our Church and our faith have been renewed and came out stronger than ever. My point in my original post was that if it got to the point where we had to go underground again, 1) could we and 2)would we have what it takes to be as successful in renewing our Church and our society. Is our contemporary Catholic sub-culture strong enough?

Pro-Life Doctors, Conscience, and the Wider Culture

According to the ethics report, physicians objecting to abortion or contraception must refer patients desiring such services to other providers (recommendation # 4); may not argue or advocate their views on these matters though they are required to provide prior notice to their patients of their moral commitments (recommendation #3); and, in emergency cases or in situations that might negatively affect patient physical or mental health, they must actually provide contraception and/or perform abortions (recommendation #5, emphasis added).In order to justify these recommendations, the committee appeals to an idiosyncratic conception of ethics and conscience. The ACOG guidelines implicitly view ethics as a matter of private emotion and sentiment, rather than as common rationality and shared practical wisdom. Against Kant’s unconditional command, Newman’s magisterial dictate, and Butler’s famous dictum (”were its might equal to its right, it would rule the world”), the ACOG committee makes conscience a mere prima facie guide. “Although respect for conscience is a value, it is only a prima facie value, which means it can and should be overridden in the interest of other moral obligations that outweigh it in a given circumstance.”

This peculiar account of conscience stands in no small tension with the view expressed by Antigone in Sophocles’ tragedy, Socrates in the Crito, and Aquinas in the Summa Theologiae. Traditionally, conscience is the supreme proximate norm for human action precisely because it represents the agent’s best ethical judgment all things considered.

In addition to the issues of conscience, though, I think this issue raises questions that confront directly what I said yesterday. If a society actually forces citizens in certain professions to perform morally reprehensible acts, then the development of an alternative subculture seems almost inevitable.

However, I think the two can stand together. It is true that as a society forces people of faith to the margins in certain areas, a kind of alternative culture in those areas will develop. I would certainly hope that if pro-life doctors were forced out of the mainstream that they would continue to practice under a different umbrella. And I would give them my patronage. But that does not absolve us of our duty to seek out and embrace the good and the true in the wider culture, wherever and whatever it is.

Monday, April 7, 2008

The Nation State and the Common Good

Here's a brief excerpt (though I recommend reading the whole thing):

Christian ethicists will commonly recognize that, in a sinful world, particular states always fall short of the ideal. Nevertheless, the ideal is presented not merely as a standard for Christian political practice but as a statement of fact: the state in its essential form simply is that agency of society whose purpose it is to protect and promote the common good, even if particular states do not always live up to that responsibility. This conclusion is based on a series of assumptions of fact: that the state is natural and primordial, that society gives rise to the state and not vice-versa, and that the state is one limited part of society. These assumptions of fact, however, are often made without any attempt to present historical evidence on their behalf.

This may be because such evidence is lacking. In this essay I will examine the origins of the state and the state-society relationship according to those who study the historical record. I will argue that the above assumptions of fact are untenable in the face of the evidence. I will examine these three assumptions in order. First, unless one equivocates on the meaning of “state”, the state is not natural, but a rather recent and artificial innovation in human political order. Second, the state gives rise to society, and not vice-versa. Third, the state is not one limited part of society, but has in fact expanded and become fused with society.

Thoughts?

Cultural Transformation

H. Richard Neibuhr, in his book Christ and Culture, sets up several different models by which it is possible to conceive the relationship between his two subjects, three of which I think are particularly helpful: (1) Christ against culture; (2) Christ of culture; and (3) Christ transforming culture. The first is the mistake of seeing Christ in total opposition to culture. It leads to a sort of isolationism, a "Holy Huddle," in which Christians turn our back on everything the world gives us and create a sort of alternative subculture. The second sees the culture as Christ's manifestation of himself in the world, and, as a result, too quickly acquiesces to whatever interpretation of goodness the culture puts forward. But the third sees Christ seeking to remake the culture, to seize on what is good in the culture and multiply it, while decreasing what is evil. This third one, I think, is the most challenging to us as Christians - we get neither the pleasure of total rebellion nor the comforts of acquiescence - but it is also the most authentic response to Christ's presence in our lives.

It is from this basis that I think we Christians have a obligation to genuinely engage the culture, and seek instances of goodness. And again, this cannot occur outside of the context of some kind of true community; without community we'll have neither the strength nor the wisdom to properly engage it. But from these communities, we have to reach out to the culture and seek its transformation, rather than simply live apart from it. We take our model from Christ, who came into the world in order to make it whole.

This plays itself out in all kinds of ways, but I'm now going to try to make this concrete by focusing on the example the arts. Many Christians seem to believe that the relative worth of a work (a film, a song, a book, a painting, anything) is inversely related to the amount of sexual, profane, or violent content it contains. However, I think the gift of community enables us (and the calling of Christ draws us) to seek what is good in a film that may contain a foul language or a sexually explicit scene (of course, I understand that this calling is tempered by the extent to which is causes any one of us to sin). And it may be that it says something true, about longing, desire, love, forgiveness, humanity, or even faith incredibly powerfully. And yet a "Christ against culture" mentality asks us to reject the piece wholesale, rather than embracing the beautiful invocation of truth rendered by the artist.

Our faith is in He who makes all things new. I think that these small communities provide a necessary component to being able to live as though that fact is true. But we have to remember that He can (and in important ways, does) transform the broader culture.

Sunday, April 6, 2008

Peter Kreeft: How to Win the Culture War

Saturday, April 5, 2008

St. Benedict: Model for Revolution

"It is always dangerous to draw too precise parallels between one historical period and another; and among the most misleading of such parallels are those which have been drawn between our own age in Europe and North America and the epoch in which the Roman empire declined into the Dark Ages. Nonetheless certain parallels there are. A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead - often not recognizing fully what they were doing - was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness. If my account of our moral condition is correct, we ought also to conclude that for some time now we too have reached that turning point. What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another - doubtless very different - St. Benedict."

There are several different theories about how changing the world happens. Some say to enter into politics and fully engage in the conversations and power struggles that take place in the world. This might be effective for some, but this approach appears to have disillusioned many in our modern world. The average person seems intimidated by "the system" that seems too big, too complicated, and too overwhelming for them to be effective in the change they are trying to make.

I think it's fascinating that St. Benedict was actually effective in changing the course of Western Civilization by taking the exact opposite approach. Rather than engaging the politics of decadent Rome and try to convince Rome of the error of its ways, he retreated from it. He spent three years in virtual solitude in Italy, as a hermit working on his relationship with God and working on his internal struggles. When he emerged from his solitude, one couldn't help but notice the holiness of this man. Like the density of a planet creates gravity that attracts its moons, so the intensity of Benedict's holiness created a gravitational field that couldn't help but attract a community of people hungry for holiness. Through these small communities, followers of Benedict lived a powerful "alternative lifestyle" and this attracted many others, creating the foundation of Western Monasticism. Ironically, the world from which Benedict retreated from came to him.

As we enter into what MacIntyre describes as a moral Dark Age in which modern man seems to have forgotten that it has purpose, let alone having a concrete understanding of what that purpose is, I think those wishing to live the moral life will have to seriously consider what it is to retreat from the world so that the world may come to us. There are certainly modern challenges, such as in the age of the Internet and mass communication, is it even possible to retreat to the mountains like Benedict did? Yet, these are merely challenges that can be worked out, not insurmountable road blocks.

Ultimately, the power of the Christian witness is that the human heart is naturally attracted to truth and beauty, and Christ literally is that Truth that makes everything beautiful. If we can provide that witness to Christ as purely as possible, without diluting it, Benedict has shown us that we really can be effective in changing the world.